Getting good sound is not a secret. It’s simply understanding everything about your role and performing your role very well.

The sound recordist’s role:

- Placing the microphones.

- Operating the recorder.

- Making sure the recording quality is good.

That’s it, really. If you do those three things right you will get good sound. The problem is doing those things right takes a hell of a lot of knowledge, experience and skills. The other problem is what works on one shoot doesn’t necessarily work on other shoots.

1. Placing the microphones:

- In general, you need to place the microphone as close to the talent as possible. This is very important.

- Start with the mic in the frame and make your DP yell at you. Move it slowly out of frame so YOU know where the frame ends.

- When booming, boom from above with the microphone angled downward aimed at the talent’s mouth.

- Know and follow the dialog.

- Know the blocking.

- Line up the mic with some reference point so you can keep it close to the talent through whatever blocking happens in the shot.

2. Operating the recorder:

- Use balanced cables for your connections

- Bit rate set to at least 16 bits, 24 bits is better

- Sample rate at least 44.1, preferably at least 48kHz

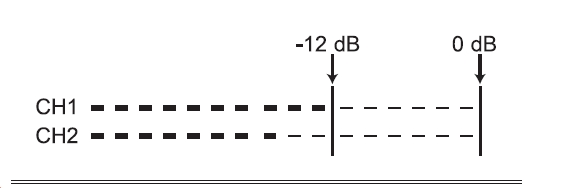

- Set the level as high as possible without clipping. Peaks should be about -6 dbFS

- Know your recorder

If your recorder doesn’t have these capabilities, you need a new one.

3. Making sure the recording quality is good:

- LISTEN. To everything. Most important.

- Good headphones are a must. (closed ear pads)

- Play some of the clips back, verify levels.

- Communicate issues immediately.

Simple, right? Not exactly, but that’s the secret in a nutshell. Use the right mic, get the mic close, set the levels correctly, follow the dialog and communicate issues.

Upcoming posts are going to go into specific details about:

- What microphone to use and why.

- Recorders, mixers, accessories.

- Boom Technique.

- Headphone reviews.

- Acoustic properties of rooms and treatment.

- Audio theory 101.

Other topics:

- Synching second system audio.

- In-camera audio recording.

- Audio bags and accessories.

- Editing audio.

- Audio Software.

And, of course, anything else you want to see discussed on Production Audio Pro.